Beyond the Curtain: Gandalf, Mortality, and Reflections from Classic Literature

Classic case of me overanalyzing anything Gandalf says pt 1.

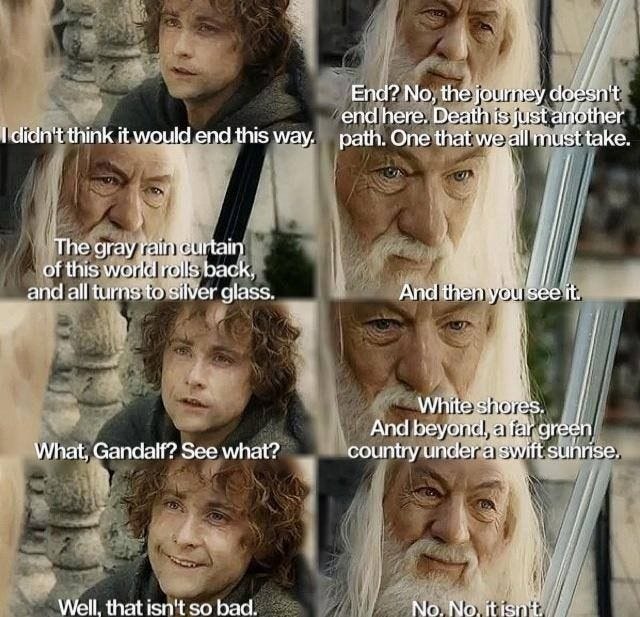

When Pippin confesses, “I didn’t think it would end this way,” he isn’t just talking about a looming battle—he’s giving voice to a question that haunts us all: What happens when this life finally reaches its end?

Gandalf’s following exchange with Pippin is more than a comforting vision; it’s a profound perspective on death itself:

Gandalf: “End? No, the journey doesn't end here. Death is just another path... One that we all must take. The grey rain-curtain of this world rolls back, and all turns to silver glass... And then you see it.”

Pippin: “What, Gandalf? See what?”

Gandalf: “White shores. And beyond, a far green country under a swift sunrise.”

In his response, Gandalf challenges the usual fear of death, reimagining it as part of an endless journey that calls not for dread, but for acceptance. His imagery suggests that death, rather than a dark conclusion, could be a beautiful curtain lifting to reveal a new and wondrous landscape.

The exchange also contains echoes of real-world philosophies and literature, each offering its own perspective on life and what might lie beyond it. In this blog, I’ll explore how Gandalf’s words resonate with these perspectives across cultures and texts, from The Epic of Gilgamesh to Moby-Dick—all suggesting that, perhaps, death isn’t the end we fear, but the next part of a journey worth embracing.

A Continuation of the Journey: Gandalf and The Epic of Gilgamesh

Gandalf’s idea of death as a “path we all must take” resonates deeply with one of humanity’s oldest recorded stories, The Epic of Gilgamesh. Written over four thousand years ago in ancient Mesopotamia, this epic follows the journey of Gilgamesh, a once-arrogant king who undergoes a profound transformation after the death of his closest friend, Enkidu. Gilgamesh’s grief propels him into a desperate quest to escape his own mortality, searching for some form of immortality that would allow him to overcome death’s inevitability.

However, Gilgamesh’s journey eventually leads him to Utnapishtim, a sage who has experienced life beyond and tells Gilgamesh the truth about death’s unavoidability. Utnapishtim’s words echo Gandalf’s calm acceptance, affirming that “there is no permanence.” Just as Gandalf comforts Pippin by presenting death as a passage rather than a dead end, Utnapishtim urges Gilgamesh to recognize that death is an intrinsic part of life, not something to be fought or feared. He advises Gilgamesh to cherish the beauty of mortal life, to find meaning in relationships, love, and accomplishments rather than endless life.

Much like Gandalf, Utnapishtim speaks of the mystery surrounding death with a sense of calm acceptance. He does not attempt to paint an exact picture of what lies beyond; but instead, he suggests that wisdom lies in embracing the mystery. For both Gandalf and Utnapishtim, death remains an integral part of the journey rather than its abrupt end. Through these two figures, we can see that the preference of accepting death, rather than fearing it, has been a part of human storytelling since ancient times.

Stoic Resilience: Gandalf and Moby-Dick

In Moby-Dick, Herman Melville’s Ishmael embodies a form of resilience that echoes Gandalf’s calm acceptance of the unknown. Ishmael, an outcast and adventurer, often ponders life’s mysteries and, like Gandalf, faces death with a resolve born of acceptance rather than dread. He famously declares, “I know not all that may be coming, but be it what it will, I’ll go to it laughing.” Ishmael’s words reflect a distinctly Stoic mindset—an acceptance of fate and a recognition of human limitations.

Ishmael finds himself repeatedly confronting death’s proximity, from life-threatening storms to the relentless pursuit of the great white whale, Moby Dick. Yet rather than succumbing to fear, Ishmael adopts a philosophical resilience, choosing to face his fate with an open mind and heart, much as Gandalf encourages Pippin to do. This parallel between Gandalf and Ishmael highlights a Stoic resilience—an ability to find purpose and peace amid life’s uncertainties and accept death as a natural part of the journey.

In Gandalf’s worldview, as in Ishmael’s, death is not an end to be feared but a passage to be embraced with acceptance and courage. Gandalf’s acceptance in the face of darkness embodies a Stoic fortitude that both comforts Pippin and serves as a powerful reminder of the human capacity to find inner peace in the face of the unknown. Similarly, Ishmael’s resolve in Moby-Dick emerges from his willingness to release himself from the need to understand or control his fate.

Just as Gandalf’s words help Pippin make peace with mortality, Ishmael’s outlook reinforces the power of embracing uncertainty rather than fighting against it. In both Tolkien’s and Melville’s worlds, the essence of Stoic resilience is about learning to see death not as an end, but as a part of life’s larger design—a destination on the horizon that, while mysterious, is neither to be dreaded nor denied. By welcoming this mysterious journey with courage, we find an inner strength that allows us to face life’s challenges with the same fortitude.

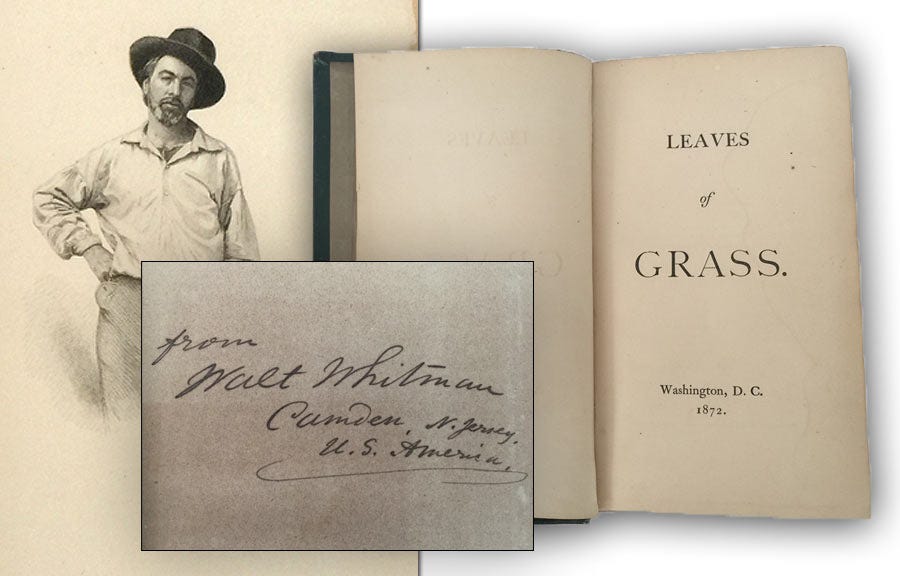

A Romantic View of Mortality: Gandalf and Leaves of Grass

Gandalf’s vision of death is romantic in essence, reminiscent of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass—Whitman’s poetry reflects a deep connection to nature and humanity, urging readers to recognize the beauty in the natural cycles of life and death.

Whitman’s poetry is often characterized by its transcendent vision, wherein death is not an ending but a transformation—a continuation of existence that intertwines with the vastness of the universe. In Leaves of Grass, he writes, “I believe a leaf of grass is no less than the journey-work of the stars.” This line evokes the idea that every part of nature, including death, is connected in a grand cosmic design. Much like Gandalf’s serene imagery, Whitman invites us to see death as part of a larger tapestry, where each life, no matter how brief, contributes to the eternal cycle of being.

Whitman’s declaration, “And as to you, death, and you bitter hug of mortality, it is idle to try to alarm me,” highlights his perspective that death is neither cruel nor harsh; it is part of the journey to be embraced as a lover, a part of the self. Just as Gandalf speaks of “white shores” and “a far green country,” Whitman imagines a “deathless” sense of self that transcends death, moving “onward, further, and further” into an endless continuum.

Both Gandalf and Whitman present death as an invitation to embrace life fully, fostering an appreciation for the moments we have. Whitman, much like Gandalf through the LOTR works, celebrates the essence of life in its totality, urging us to revel in every experience, whether joyous or sorrowful. His poetry is infused with a Romantic ideal that emphasizes emotional depth and the interconnectedness of all living things, much like the fellowship and bonds forged among the characters in Tolkien’s Middle-earth.

Eastern Reflections: Gandalf and the Tao Te Ching

In the Tao Te Ching, the foundational text of Taoist philosophy attributed to Laozi, we encounter a profound understanding of the cyclical nature of existence that resonates deeply with Gandalf’s perspective on death. Laozi articulates this wisdom succinctly when he states, “Life and death are one thread, the same line viewed from different sides.” Just as Gandalf invites Pippin to envision a tranquil and beautiful landscape beyond death, Laozi invites us to see life and death as a continuous dance—each step essential to the rhythm of existence.

Notably, in the Taoist worldview, life and death are not opposing forces; rather, they are interconnected phases of the same cycle. This perspective encourages us to embrace death not as a fearful conclusion but as a harmonious part of the broader tapestry of life. This reflection encapsulates the essence of Gandalf’s assertion that death is merely “another path”—an integral part of a continuous journey rather than a definitive end.

Taoism also teaches the value of non-action, or wu wei, which is not a call for passivity but an encouragement to move with the flow of life rather than against it. Gandalf embodies this principle, demonstrating an understanding that death, like life, should be approached with grace and acceptance. He reassures Pippin that while the journey beyond may be unknown, it is not to be feared. Instead, Gandalf’s calm demeanor reflects the wu wei approach—an acceptance of what is to come, embracing the transition with poise rather than resistance.

The imagery that Gandalf employs—“white shores” and “a far green country under a swift sunrise”—is deliberately evocative, suggesting a realm where tranquility and beauty reign. This notion parallels the Taoist belief in the importance of harmony with the universe. Laozi emphasizes that by aligning ourselves with the natural flow of life, we can find peace and serenity. In both Gandalf’s vision and the teachings of the Tao Te Ching, there is an invitation to surrender to the mysteries of existence, recognizing that resisting the natural order only brings about suffering and discontent.

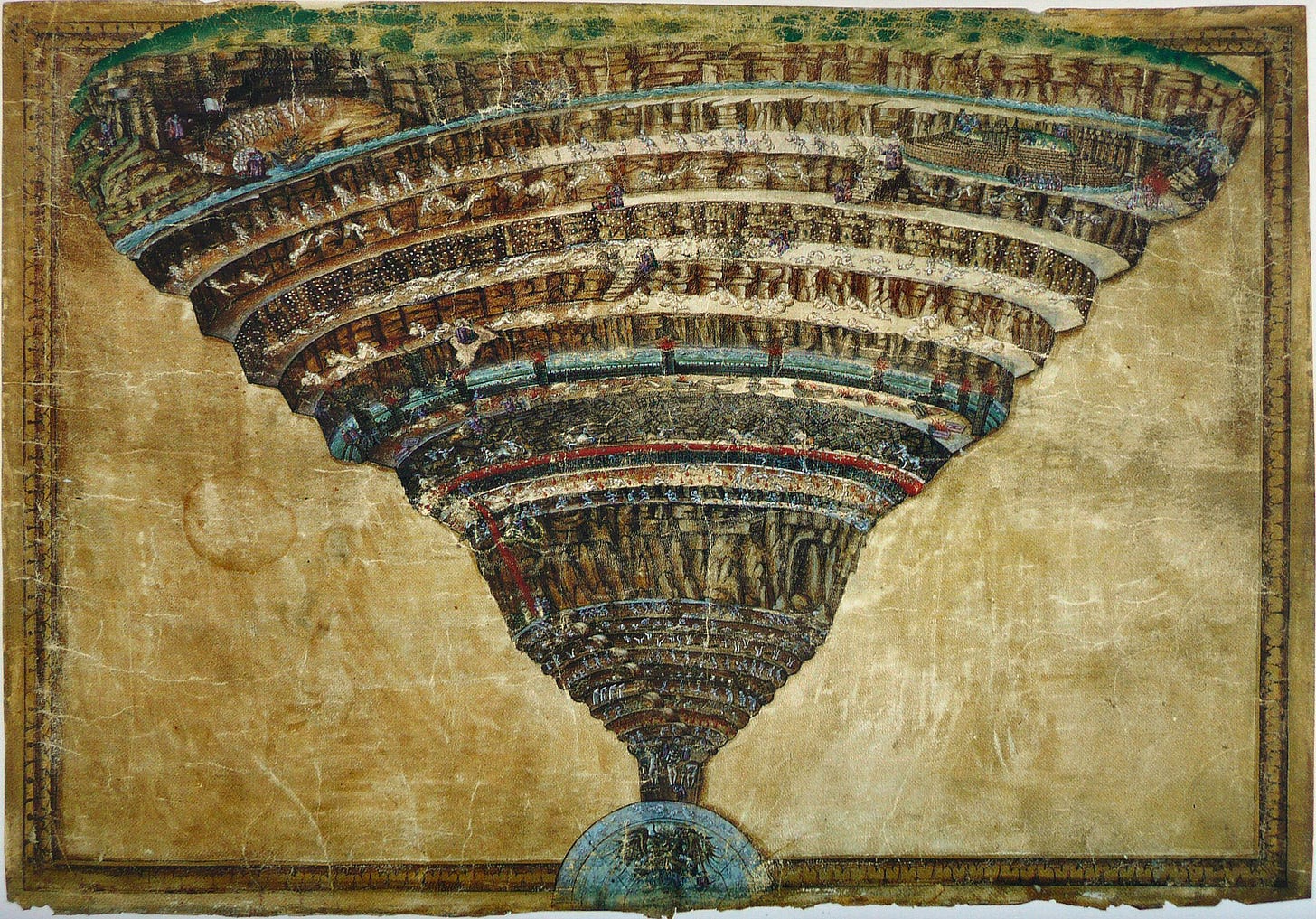

The Mystery of Death: Gandalf and The Divine Comedy

Dante Alighieri’s The Divine Comedy, is a seminal work that delves into the nature of the afterlife and the journey of the soul. As Dante traverses the realms of the afterlife—Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso—he uncovers profound insights about sin, redemption, and the ultimate goal of the human spirit: reunification with the divine. Much like Gandalf’s assertion that death is merely “another path,” Dante’s journey underscores the idea that the end of earthly life is not a finality but a transformative experience that leads the soul toward enlightenment and peace.

In the climactic moments of Paradiso, Dante writes, “The beauty I beheld transcends all thought / Beyond the mortal’s reach.” This line encapsulates the ineffable nature of the divine and the transcendence that awaits beyond the veil of death. Similarly, Gandalf offers Pippin a glimpse of a beautiful and serene afterlife, evoking images of “white shores” and “swift sunrises” that suggest a realm of profound peace and joy. Gandalf, like Dante, presents death not as a loss but as an entry into a place beyond sorrow, where darkness and suffering are left behind. The beauty of this far country speaks to the soul’s desire to return to its origin, a longing both Gandalf and Dante’s guide satisfy with poetic, transcendent imagery.

The journey through The Divine Comedy also mirrors the struggle against despair and the quest for understanding that characters in The Lord of the Rings must navigate. Dante’s journey is ultimately one of redemption, emphasizing the belief that even in the face of sin and suffering, there is hope for transformation and reunion with the divine. This is akin to Gandalf’s reassurance to Pippin that death is not an end to be feared, but a necessary step in a much larger narrative. Gandalf’s words suggest that the journey continues beyond the constraints of the physical world, much like Dante’s own progression from the darkness of hell into the light of paradise. In both narratives, the soul's journey through the trials of existence culminates in a return to a state of grace and harmony.

A Hopeful Mystery

Gandalf’s words to Pippin remind us that, even as we face the unknown, there is space for beauty and hope beyond fear. In his vision, he offers a glimpse of death as a continuation rather than a termination—a peaceful path leading to a place that, although shrouded in mystery, feels like home. Through Gandalf, Tolkien taps into a universal sense of curiosity, a sense that our journey doesn’t end here and that what lies beyond is worthy of contemplation, not dread.

This perspective on death transcends Middle-earth and resonates within our own world, inviting us to consider mortality not as an end but as a part of a greater whole. In a world where we often feel the weight of impermanence, Gandalf’s wisdom provides comfort. His words encourage us to look at life as a journey of courage and purpose, where even the moments of darkness lead to something bright and beautiful.

They say, as the great writers have said across time and place, that death is neither end nor enemy. Perhaps, as Pippin finally realizes, “Well, that isn’t so bad.”

ad astra,

Maryam ✨ tomesandtravels

Instagram | Goodreads |YouTube